I have to give a big shout out to one of my mentors. We've never met in person, but Chip Thomas sparked something in me the first time I encountered a photo of his wheatpaste work on the web.

I was struck with the graphic simplicity, the scale, the statement. I didn't know who the artist was, but I knew the art was important. I felt it.

I've always been drawn to street art. I think I love the democracy of it. The rebellion. The audacity. When I was a teenager in a small New Mexico town, I embraced the voice that vandalism gave me. Painting in the middle of the night felt freeing, an escape. As I got older and explored photography, I amassed hundreds of photos of buffed graffiti, seeing a beauty in the unspoken back-and-forth dialogue between street artists and authority. I see street artists of every kind as change agents, speaking bravely in a world where so many voices are unheard.

And when I saw Jetsonorama's work, I got chills. What a voice. What audacity. What truth. Powerful images from Dinétah that truly amplified a cultural voice that, in the New Mexico four corners of my childhood, was often ruthlessly silenced.

So I played with wheatpaste. I googled recipes. I contacted Chip. I planned a project with my fifth grade class in southern New Mexico.

Out of that initial inspiration, my fifth grade students from a primarily Mexican-American, low-income, underserved school in Las Cruces, New Mexico partnered with a mentor high school class my mom was teaching in Farmington, New Mexico. We communicated back and forth about the project.

My students from southern NM were also learning about Native American history at the time, and I was shocked to find that some of them thought Indians were a people of the past, and that they weren't alive today. We looked at Chip's work together. We read the work of native poets. We invited native guest speakers into our classroom. Our art project dialogue turned into something much more. Diné students from Farmington were able to write letters to my students and describe their experiences as native youth. Their voices were current, relevant, and something my students could understand and learn from. They walked my class through the steps of a collaborative project, but they also brought an awareness of New Mexican culture that my students hadn't known existed. Those letters were transformative.

And that's the thing. Art is transformative. Art starts conversations. Art stirs ideas. Art creates a space for questioning, for debate, for resistance. Art amplifies voices. Art builds alliances. Chip's inspiration ignited a spark that turned into a connection - a project spanning from southern to northern New Mexico, engaging kids, teachers, and community members from all kinds of backgrounds and cultural experiences.

Recently, Chip was profiled on Fronteras in an article about his art and his activism. I love that he is so representative of the complexity of the Southwest. Our land is steeped in a history of cultural collisions, and so much of that history is tragic - something to mourn, a legacy of racism, genocide, and injustice. But it's also a land where people of different cultures have chosen to respect each other, to live together in a space of shared reverence for the harshly beautiful landscapes, to connect, to work together for more just and equitable communities.

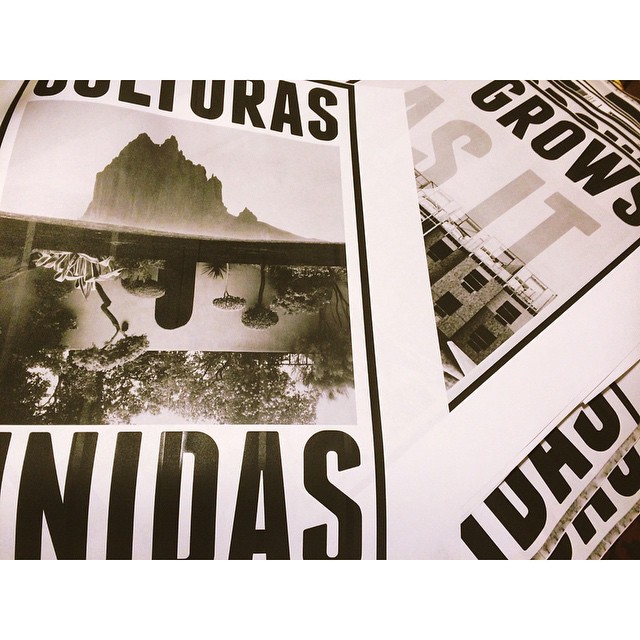

This last year, I have been working on a personal wheatpaste project. It is based on New Mexico symbols - our pledge, state motto, etc. I've pasted from Las Cruces to Farmington, with stops in Albuquerque, on the stretch of highway between Gallup and Grants, and in Truth or Consequences. I'm working on my wheatpaste voice and hope to develop more projects that address the emotional, political, and spiritual issues that impact my beloved New Mexico.

Thanks, Chip.